Fingers

and Toes – a Digital Quest

Chris Price

Chris Price

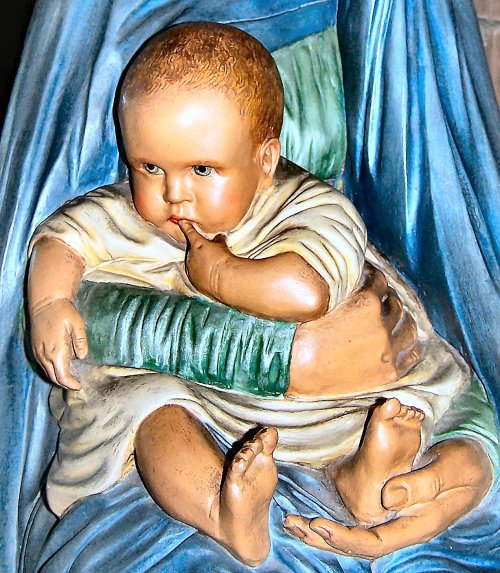

No-one who has been into St Faith’s can

fail to have noticed the lovely statue of the Madonna and

Child which stands in the Lady Chapel, and which we know

as the Rabbit Madonna as there are two bunnies depicted,

one at each of Mary's feet. Almost equally certainly, few

will be unaware that the endearing figure of the infant

Jesus has one toe short on his right foot. Why this should

be so has always been a puzzle, but recent events have

provided a possible explanation, as well as shedding more

light on the provenance of the statue and of its sculptor,

Mother Maribel of Wantage.

The unravelling begins with a recent visit by this writer to Rufford Old Hall, a fine National Trust property in Lancashire. Our visit coincided with an entertaining talk by a lady guide in the Great Hall. She focused in depth on the unique ‘movable’ screen: a massive structure carved from black oak and designed to hide the sight of scurrying servants from the great and the good feasting in the hall. This was familiar from a previous visit – until she mentioned that there were three deliberate flaws in the intricate carving: two on the front and one at the rear. The front two were decorative panels carved the wrong way up; the third, which she challenged those present to find, turned out to be on the figure of an angel high up on the rear of the massive structure. Peering into the gloom, it was possible to see that the figure had an extra finger on one hand. Both oddities may clearly be seen on the photographs above.

What struck a chord was the guide’s confident statement that the aberrations were deliberate imperfections, incorporated by pious craftsmen to demonstrate their belief that only God could create perfection. The inference was that this was a common practice.

It was some time later that I began to wonder whether the missing toe on our statue might be another example of this practice. So began a piece of research which, at the time of writing, has provided some answers but has also provided further mysteries.

Apart from the digital deficit issue, we had long hoped to find out more about the ‘Rabbit Madonna’: clearly the time had come to dig deeper. I found the contact details for the Community of St Mary the Virgin, an order of Anglican nuns in Wantage, Berkshire. We had known that this was the home of Mother Maribel, since ‘C.S.M.V.‘ is inscribed on the base of the statue plinth. I fired off an email, asking if they could fill in any details about the piece in general and the toe shortage in particular. It was not long before a reply came. The sister who wrote hadn’t heard of the statue, but hoped it might be listed in their inventory of Maribel’s works. She asked for photos and dimensions and ended with this entertaining paragraph.

‘It is quite probable that the “sick cow” story is true as M. Maribel had a wicked sense of humour; her studio was in the farm buildings and had been a cowshed.’

The reference is to words from our church website, which I had quoted in my mailing. It states that, in order to discourage visitors, Mother Maribel had posted a notice saying ‘sick cow’ on her studio door! This revelation from the nuns naturally spurred me on in pursuit of more information. I sent photos and dimensions and soon received further enlightenment. Sister Jean Frances wrote that although she wasn’t supposed to be involved in the investigation, she was intrigued! She had now found mention in an inventory of two statues, 3’ tall, entitled ‘Seated Madonna and Child with rabbits, made in 1925, cast in plaster: Winchester and Portsmouth’.

She wondered if we knew when and how the statue came into our possession. The fact is that we have yet to find this out. I had thought for some reason that it might have been in the 1950s, but there seems to be no record in registers, magazines or church histories. Were the statues made for churches in Winchester and Portsmouth? Here again, not even Google has yielded anything of use to me or to co-sleuth John Woodley, so that the story of the statues (and obviously ‘ours’ is one of the pair) is unfinished, not least concerning the Madonna’s journeying between 1925 and when she arrived in our Lady Chapel. Investigations are ongoing and Wantage has promised further help.

The other intriguing matter is that of the ‘deliberate imperfection’ theory. In pursuit of further enlightenment, I surfed the web, and found plenty of references to the concept. It is seemingly a Muslim practice, notably but not exclusively in the weaving of Persian rugs, and seems also to be a feature of American Amish art. But I cannot find any reference to it whatsoever in connection with mainstream Christian art, other than a Wikipedia reference to the Rufford imperfections. Undeterred, I emailed Rufford to see if they could fill the gap, and am promised an answer.

Finally, a further thought entered my consciousness a few days ago. An equally fine furnishing of our church is of course the splendid Salviati reredos above the High Altar. Curiously, this also has its imperfections. The folding ‘wings’ of the reredos feature angels looking inwards towards the centre – but two of them, one on each side, are facing outwards. It has been assumed that when the reredos was restored and repainted, these two figures were accidentally transposed. But the similarity to the Rufford panel carvings is nevertheless striking. The jury are out over the panels - but there’s more. The side folding wings are decorated with a series of what are clearly hand-painted ‘ihs’ monograms (the first three letters of the Greek name for Jesus, although often taken to mean Iesu Hominum Salvator – Jesus saviour of mankind). One of them, on the right hand wing, lacks the ‘i’ in the lettering. A careless apprentice of Salviati, which escaped quality control – or another deliberate imperfection?

As one question is answered, others seem to emerge. The quest continues, and subsequent findings will of course be published. Meanwhile, if any of ye can shed further light on these matters, ye are to declare it...

The unravelling begins with a recent visit by this writer to Rufford Old Hall, a fine National Trust property in Lancashire. Our visit coincided with an entertaining talk by a lady guide in the Great Hall. She focused in depth on the unique ‘movable’ screen: a massive structure carved from black oak and designed to hide the sight of scurrying servants from the great and the good feasting in the hall. This was familiar from a previous visit – until she mentioned that there were three deliberate flaws in the intricate carving: two on the front and one at the rear. The front two were decorative panels carved the wrong way up; the third, which she challenged those present to find, turned out to be on the figure of an angel high up on the rear of the massive structure. Peering into the gloom, it was possible to see that the figure had an extra finger on one hand. Both oddities may clearly be seen on the photographs above.

What struck a chord was the guide’s confident statement that the aberrations were deliberate imperfections, incorporated by pious craftsmen to demonstrate their belief that only God could create perfection. The inference was that this was a common practice.

It was some time later that I began to wonder whether the missing toe on our statue might be another example of this practice. So began a piece of research which, at the time of writing, has provided some answers but has also provided further mysteries.

Apart from the digital deficit issue, we had long hoped to find out more about the ‘Rabbit Madonna’: clearly the time had come to dig deeper. I found the contact details for the Community of St Mary the Virgin, an order of Anglican nuns in Wantage, Berkshire. We had known that this was the home of Mother Maribel, since ‘C.S.M.V.‘ is inscribed on the base of the statue plinth. I fired off an email, asking if they could fill in any details about the piece in general and the toe shortage in particular. It was not long before a reply came. The sister who wrote hadn’t heard of the statue, but hoped it might be listed in their inventory of Maribel’s works. She asked for photos and dimensions and ended with this entertaining paragraph.

‘It is quite probable that the “sick cow” story is true as M. Maribel had a wicked sense of humour; her studio was in the farm buildings and had been a cowshed.’

The reference is to words from our church website, which I had quoted in my mailing. It states that, in order to discourage visitors, Mother Maribel had posted a notice saying ‘sick cow’ on her studio door! This revelation from the nuns naturally spurred me on in pursuit of more information. I sent photos and dimensions and soon received further enlightenment. Sister Jean Frances wrote that although she wasn’t supposed to be involved in the investigation, she was intrigued! She had now found mention in an inventory of two statues, 3’ tall, entitled ‘Seated Madonna and Child with rabbits, made in 1925, cast in plaster: Winchester and Portsmouth’.

She wondered if we knew when and how the statue came into our possession. The fact is that we have yet to find this out. I had thought for some reason that it might have been in the 1950s, but there seems to be no record in registers, magazines or church histories. Were the statues made for churches in Winchester and Portsmouth? Here again, not even Google has yielded anything of use to me or to co-sleuth John Woodley, so that the story of the statues (and obviously ‘ours’ is one of the pair) is unfinished, not least concerning the Madonna’s journeying between 1925 and when she arrived in our Lady Chapel. Investigations are ongoing and Wantage has promised further help.

The other intriguing matter is that of the ‘deliberate imperfection’ theory. In pursuit of further enlightenment, I surfed the web, and found plenty of references to the concept. It is seemingly a Muslim practice, notably but not exclusively in the weaving of Persian rugs, and seems also to be a feature of American Amish art. But I cannot find any reference to it whatsoever in connection with mainstream Christian art, other than a Wikipedia reference to the Rufford imperfections. Undeterred, I emailed Rufford to see if they could fill the gap, and am promised an answer.

Finally, a further thought entered my consciousness a few days ago. An equally fine furnishing of our church is of course the splendid Salviati reredos above the High Altar. Curiously, this also has its imperfections. The folding ‘wings’ of the reredos feature angels looking inwards towards the centre – but two of them, one on each side, are facing outwards. It has been assumed that when the reredos was restored and repainted, these two figures were accidentally transposed. But the similarity to the Rufford panel carvings is nevertheless striking. The jury are out over the panels - but there’s more. The side folding wings are decorated with a series of what are clearly hand-painted ‘ihs’ monograms (the first three letters of the Greek name for Jesus, although often taken to mean Iesu Hominum Salvator – Jesus saviour of mankind). One of them, on the right hand wing, lacks the ‘i’ in the lettering. A careless apprentice of Salviati, which escaped quality control – or another deliberate imperfection?

As one question is answered, others seem to emerge. The quest continues, and subsequent findings will of course be published. Meanwhile, if any of ye can shed further light on these matters, ye are to declare it...

September 5th, 2015