Page

Updates:

March 15th, 2005

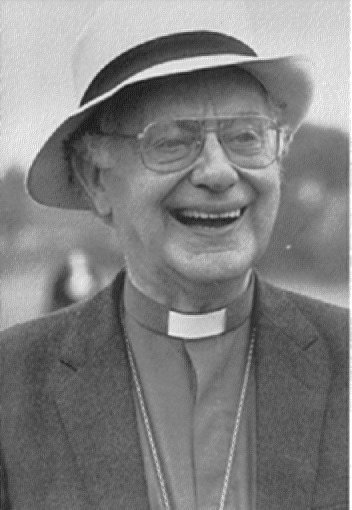

The first update is a full and

perceptive obituary notice dating from 2000. The

second, a short poem, is an impression of Robert Runcie's

enthronement

in Canterbury Cathedral in 1980, scenes from which feature

on the DVD 'Lord

Runcie Remembered' referred to in the previous update.

Robert

Runcie, who has died aged 78, might

prove to have been

the last of the patrician archbishops of Canterbury. Tall and

elegant,

urbane and witty, he had the sort of charisma - not always

evident on television

- that made everyone he spoke to feel special. People loved

him for it.

Yet there was always that subtle formality that set him apart

in church

circles from the casual familiarity with which Christian names

are almost

universally used. Old friends called him Bob, newer friends

called him

Robert; but those who had no right rarely presumed to refer to

him as anything

but "the archbishop".

He was a workaholic perfectionist,

demanding impossibly

high standards of himself and of his staff. Only his most

intimate friends

knew the true depth of the spiritual faith and toughness which

sustained

him through punishing schedules of work, public engagement and

overseas

travel. The vulnerability was there, but the toughness also

enabled him

to withstand the constant attacks from the tabloid and

rightwing press

that were mounted on him and his family throughout the middle

years of

his time at Lambeth Palace.

For a short honeymoon period, it had

delighted

the media that this pig-keeping, ex-tank commander archbishop

should officiate

at a royal wedding, welcome the Pope to Canterbury, and deploy

Terry Waite

to rescue hostages. But the dramatic change came when he

preached penitence

and reconciliation at the service of thanksgiving after the

Falklands war

in 1982, instead of the triumphalism the press and politicians

had looked

for. From then on, all his considerable achievements were set

against a

background of a tabloid venom - aided and abetted, many

believed, by a

mafia of homosexual Anglo-Catholics and rightwing politicians.

His survival

was a triumph of intelligence, integrity and courage.

His instincts were patrician, but not his

origins.

Runcie grew up in Crosby, now a suburb of Liverpool, the

youngest child

of an electrical engineer at the local Tate and Lyle sugar

factory. He

won a scholarship to the local Merchant Taylors' School where

he was an

ideal pupil: clever, well-mannered and athletic. His parents

were not churchgoers.

His Scottish Presbyterian father referred to Church of England

clergymen

as "black beetles". Robert's conversion came about by

following a girl

on whom he had an adolescent crush to confirmation classes.

His older sister

steered him in the direction of a strongly Anglo-Catholic

church, and within

a short space of time he was fully involved in the rituals of

smells and

bells and catholic spirituality.

His father became blind and had to retire

early,

and the family was short of money. But a scholarship took

Runcie to Brasenose

College, Oxford, to read classics, where his time was

interrupted by war

service. Out of affection for his Scottish-born father, he

volunteered

to join a Scottish regiment, and was startled to be recruited

as officer

material for the Scots Guards. It proved a significant part of

his education.

As a lower-middle-class boy from Liverpool he at first had a

hard time

of it, but quickly learned form. His platoon and his

fellow-officers -

among them names like William Whitelaw - soon discovered that

he was good

company and an amusing and talented mimic.

In later years, Runcie used to say he was

probably

the first Archbishop of Canterbury since Thomas à Becket to

have

been into battle. The Third Battalion of the Scots Guards

landed at Normandy

soon after D-Day in June 1944, and fought their way to the

Baltic. En route

Runcie won the Military Cross for wiping out a German gun

emplacement while

under heavy fire, though this became something of an

embarrassment to him

when he was archbishop. He would have preferred it to have

been for his

action the previous day when, at the risk of his own life, he

had pulled

one of his platoon out of a burning tank.

After returning to Oxford, where he

gained a first

class degree in Greats and learned a classical liberalism

which shaped

his thought for the rest of his life, he went to Westcott

House, the theological

college in Cambridge. There the other ordinands - trained by

Kenneth Carey

- included Hugh Montefiore, Simon Phipps, Patrick Rodger,

Graham Leonard,

Stephen Verney and Victor Whitsey. Runcie did not, however,

take a degree

in theology. It was possibly not a wise decision, for he ever

afterwards

regarded himself as a theological lightweight, despite the

years teaching

in theological colleges, and he kept up with theological

reading in a way

that few other clergy ever do.

After two happy years as a curate in

Gosforth,

Tyneside, he rejoined Carey at Westcott House, as chaplain,

later vice-principal.

In 1956 he was elected fellow and dean of Trinity Hall,

Cambridge. There

he married Rosalind and the first of their two children was

born. Four

years later he was appointed principal of Cuddesdon

theological college,

near Oxford.

During his 10 years at Cuddesdon he not

only humanised

what had been a repressively monastic establishment, but

raised its academic

standing and strengthened its links with Oxford University.

This was during

a period when he was also having to steer his students through

the furore

caused by the then Bishop of Woolwich John Robinson's 1963

book, Honest

To God. Unsurprised by Robinson's theology, Runcie welcomed

the debate

it produced. In future years as a bishop and archbishop he

constantly drew

on ex-students from Cuddesdon when making appointments to his

staff.

In 1970 he became Bishop of St Albans. By

this

time his workaholic lifestyle was well established, though

always hidden

behind his easy friendliness. He was a popular bishop in a

flourishing

diocese. While there he became chairman of the central

religious advisory

committee, answering to both the BBC and the IBA. He was also

appointed

chairman of the Anglican-Orthodox joint doctrinal commission,

which was

to foster his affection for the Orthodox churches.

Always finding it hard to take himself

seriously,

he seems to have been genuinely astonished when, in 1979,

after nine years

in St Albans, the then prime minister, Margaret Thatcher,

asked if she

could forward his name to the Queen to succeed Donald Coggan

as Archbishop

of Canterbury. He was the first archbishop to have been chosen

by the church

itself under the new crown appointments system, and it took

him three weeks

to say yes.

He brought with him to Lambeth his

chaplain, Richard

Chartres (now Bishop of London), a considerable support and

influence in

shaping those early days. Runcie had a gift for strategic

planning, organisation

and delegation unusual in a Christian leader. He soon

recognised that,

if a modern Archbishop of Canterbury were to satisfy the huge

expectations

of his office, he would need the staff and resources of an

efficiently

run establishment, and must always be properly briefed. The

talented team

at Lambeth Palace included Terry Waite; but his staff found

(and would

complain in private) that the more he delegated, the more

extra work he

took on. Among other demands, he promised - and just about

managed - to

visit every province of the world-wide Anglican communion

before the Lambeth

Conference of 1988.

In his first three years at Lambeth he

was scarcely

out of the headlines. The saga of Terry Waite as "the

archbishop's special

envoy" extricating three missionaries being held hostage in

Iran captured

the public imagination during Christmas 1980. It took two

months of Waite's

negotiating skills to gain their release, which Runcie was

able to announce

at a dramatic moment in the middle of the 1981 February

General Synod.

That same year he married the Prince and

Princess

of Wales, taking centre stage with them in all the

international publicity

that surrounded that event. He was concerned at the time at

the extreme

youthfulness of Diana, but hoped she would grow into her role.

He later

said he had found Prince Charles "disenchanted" with the

Church of England,

and Diana not naturally religious, but he kept in contact with

the couple

and, at Charles's request, did his best to help Diana.

A year later Runcie was instrumental in

inviting

Pope John Paul II to Britain and was howled down by anti-

papists in his

native Liverpool for doing so. By this time Runcie had

developed a personal

friendship with Basil Hume, the Cardinal Archbishop of

Westminster, and

together they and their respective staff planned the visit.

Runcie held

strongly that the Pope should experience Anglican worship

while in England.

A eucharistic service was ruled out by the Pope, but gradual

agreement

was reached about a great "celebration of faith" to take place

in Canterbury

Cathedral. This was the time of the Falklands war, and plans

for the Pope's

visit were complicated by the invasion of the islands by Roman

Catholic

Argentina. The Vatican declared the visit would have to be

cancelled if

the crisis continued, and the whole project became uncertain

until, with

less than a week to go, the British government offered to

withdraw from any official participation

in the

visit. On May 29 1982 the Pope arrived in Canterbury, to be

welcomed by

Runcie and escorted to the high altar of the cathedral. It was

a historic

service: an act of reconciliation which marked how far the

relationships

between the Anglican and Roman churches had eased since the

Second Vatican

Council. It was probably Runcie's high point in public esteem

when he was

seen to be guiding the Pope through the

unfamiliar English liturgy.

Victory in the Falklands followed soon

after.

At the service of thanksgiving in St Paul's Cathedral, Runcie

reminded

the congregation that war was a terrible thing, and "people

are mourning

on both sides in this conflict". He deeply offended members of

the Conservative

government, who were expecting triumphalism, and much of the

rightwing

establishment, political and press, never forgave him for it.

In the following

months, government and media began to realise that on many

issues, particularly

those to do with unemployment and deprivation, Runcie and a

growing number

of other bishops were becoming a political force.

When the report of the Archbishops'

Commission

on Urban Priority Areas, Faith in the City, was published in

1985, it left

Mrs Thatcher and her government in no doubt that the concerned

leadership

of the Church of England could not endorse Conservative

policies which

did so little to alleviate the misery of poverty and bad

housing in the

inner cities. It was blown up into a church versus government

row, with

Runcie receiving most of the opprobrium. But while the report

criticised

both the state and the church for its record in the inner

cities, it was

not mere words. In response to its call, the Church of England

raised over

£18m to support hundreds of local projects to help the urban

poor.

It was often said at this time that,

because the

Labour party was in disarray, the Church of England was

becoming the real

opposition in the country. The archbishop himself was often

under criticism

for "not giving a clear lead" (ie not taking a conservative

stand) on a

number of moral and theological issues, as well as on the

vexed question

of the ordination of women.

The rightwing campaign against him took a

nasty

turn when it began to focus on his marriage and his wife.

Lindy, from the

outset, had made it clear that she was her own woman. She

rarely accompanied

Runcie on the weekends he spent at the Old Palace in

Canterbury, because

her interests were in London. She only went with him on his

overseas visits

when she had been invited to perform as a concert pianist. A

tabloid newspaper

had splashed privately-taken pictures of her, including one in

evening

dress draped across a piano, and another in a swimsuit; and

the implications

were that the marriage was breaking up, and Runcie should

resign as archbishop.

The persecution, for such it was, surfaced at intervals over

the middle

years of Runcie's archiepiscopate, until he and Lindy were

forced to issue

a formal statement that they had been "a happily married

couple for nearly

30 years, and we both look forward to our rewarding

partnership continuing

for the rest of our lives".

On marriage, as on many issues, Runcie

was more

liberal than conservatives in church and state really liked.

He had long

advocated re-marriage in church after divorce in cases where

partners really

wanted to make a new Christian marriage; but it often looked

as though

his liberal intellect was in tension with his catholic,

conservative and

pastoral instincts. He refused to condemn, as many

traditionally-minded

Christians would have liked him to do, the Bishop of Durham's

radical theology,

though at the same time he privately deplored Dr Jenkins's

pastoral ineptitude

in coming out with such views at the great Christian festivals

of Easter

and Christmas.

He showed cautious sympathy for

homosexuals. In

a church where many good priests were known to be of that

orientation,

he had homosexual friends and ordained men whom he suspected

were gay,

but he always preferred a policy of "don't ask". Accused by

angry evangelicals

of contravening the church's teaching, he claimed that he had

never "knowingly

ordained anyone who told me they were a practising homosexual

and living

in a partnership as if it was a marriage". His refusal to

support openly

gay clergy drew their animosity, and Runcie admitted that he

could never

quite trust them not to stab him in the back.

In General Synod debates on national and

international

affairs, he often knew too much of the complexities of the

situation from

his many contacts in government, the Foreign Office and

overseas to be

able to endorse some of the simplistic solutions the Synod

wanted to offer.

And on the subject of ordaining women, many people thought him

handicapped

by his affection for the deeply conservative Orthodox

churches.

Only reluctantly did he accept that he

must vote

in the General Synod for women priests. The church was deeply

divided on

the issue, and both sides were often frustrated by what they

saw as the

archbishop's "nailing his colours to the fence" and refusing

to come clean

about his own real views. His traditionalist instincts, his

radical sense

of justice, and his deep fear of a split church were all in

tension. With

hindsight it is probable that his long refusal to commit

himself helped

to limit the damage when the vote for women priests was

eventually passed.

During all these years he was incessantly

travelling

throughout the Anglican communion. It should have been Terry

Waite who

set up and accompanied him on these tours. But increasingly

Waite had become

involved in his attempts to rescue hostages held in the Middle

East. He

had been successful in rescuing the three missionaries from

Iran, and in

negotiating the release of four Britons held in Libya. He then

turned his

attention to hostages held in the Lebanon, and got out of his

depth in

Lebanese, Iranian and American politics as he attempted to

secure the release

of more western hostages in Beirut. Runcie defended his work,

but grew

increasingly uneasy about it, both for the sake of Waite's

personal safety,

and because the Lambeth Conference, which Waite should have

been organising,

was fast approaching.

Suspicions surfaced that the Americans

were using

Waite to cover up an arms deal with Iran, and Waite, in a

defiant attempt

to clear his name, and against Runcie's advice, went on

another expedition

to Lebanon, where he was himself taken hostage. Not knowing

where he was,

or whether he was dead or alive, cast a shadow over the last

three years

of Runcie's archiepiscopate.

A few months later, with criticism of

Runcie from

the conservative - and anti-women priests - wing of the church

running

high, an anonymous preface was published in Crockford's

Clerical Directory,

which accused him with donnish venom of always taking the

liberal line

of least resistance on all issues, and of appointing a

succession of liberal

elitist bishops who were theologically unsound. It was quite

clearly the

work of an academic disappointed at not being offered high

office in the

church, and Runcie, like many others, quickly guessed that the

author was

the Rev Dr Gareth Bennett, an Oxford theologian, a closet

homosexual and

an Anglo-Catholic, whom he had long regarded as a personal

friend. Runcie,

challenged by a reporter about the preface, delivered one of

the most apt

aphorisms to fall from the mouth of an archbishop: "In my

father's house

are many mansions - and all of them are made of glass." The

Bennett affair

was the second dark shadow to fall across Runcie at Canterbury

and was

made darker when Bennett, pursued by the media and fearing the

inevitable

exposure, committed suicide.

However, there was genuine acclaim by the

assembled

bishops of the whole Anglican Communion when Runcie opened the

1988 Lambeth

Conference in Canterbury. He had been working towards it from

the time

he had been made archbishop. Before it took place there had

been grave

warnings that this would be the last of the 10-yearly

conferences, for

it was said that the Anglican communion was being torn apart

by tensions

over doctrine, particularly with regard to the ordination of

women, and

cultural differences. For Runcie the conference was a great

personal triumph,

and the climax of his career. His astonishing energy, his

warmth and humour,

and his skill in handling difficult issues, not only held the

huge gathering

of bishops together for three weeks, but ensured that they

would go away

determined to keep the Anglican communion intact, and meet

again in 1998.

Carefully choosing his moment, he retired

at the

beginning of 1991. He was given a life peerage, and with Lindy

went to

live in St Albans. His diary remained full. He was able to

resume an occupation

he had several times enjoyed before becoming archbishop:

sailing as guest

lecturer on Swan Hellenic cruises. He was in constant demand

for lecture

tours in America, for semi-official visits to Eastern Europe

and Africa,

and for television programmes. The absence of any news of

Terry Waite remained

a continuing sadness until November 1991, when Runcie was at

last able

to welcome him home.

In retirement he had two health scares.

He had

to be flown home from Salt Lake City with a recurrence of

cellulitis, a

serious condition originally caused 30 years before by a

crop-sprayed blackberry

thorn, and exacerbated by a splinter. During his stay in the

American hospital

he, for the first time, received the sacrament consecrated by

a woman priest

and "wondered why we'd been fussing about it". Then, in 1994,

he had a

prostate operation which revealed some cancer, but with a good

prognosis.

Though he had already been the subject of

three

biographies, none of the authors of them had been given access

to his official

papers. For the sake of future historians he accepted there

should be a

fully authorised biography to take its place with those of his

predecessors,

and invited Humphrey Carpenter to write it.

When the book was almost complete, Runcie

was

horrified that, far from being the seriously researched

history of his

episcopate he had expected, much of it, he felt, was simply

transcribed

conversations and gossip, including a number of old

indiscretions Runcie

had given off the record about the royal family. He also

thought Carpenter

had exaggerated the way Runcie had used staff and friends to

research and

draft most of his addresses as though he had few ideas of his

own, and

had failed to understand the importance of the archbishop's

overseas visits,

and his extraordinary personal achievement at the Lambeth

Conference. Runcie

reluctantly accepted that it was Carpenter's book, and he had

made no real

stipulations about the form it should take. He did, however,

write a postscript

for it stating: "I have done my best to die before this book

is published...

the writer... who so brilliantly evoked the atmosphere of

Oxford in the

1940s does not seem to me to have grasped what it was like to

be Archbishop

of Canterbury in the 1980s."

Once again, Runcie was in the tabloids,

and under

fire from his former critics, particularly about the remarks

he had made

about Prince Charles and Diana, and his admission that, yes,

he had ordained

homosexuals. Undoubtedly the book sold well because of it, but

it was hard

to see it as other than a piece of opportunism on Carpenter's

part. Perhaps

the task was too great, and the subject too enigmatic, despite

Runcie's

disarming frankness. But that book will not stop many church

members looking

back on the Runcie era as one of the most colourful and

distinguished periods

of recent church history.

He is survived by his wife, son James and

daughter

Rebecca.

•Rt Rev and Rt Hon Robert Alexander

Kennedy

Runcie, Lord Runcie of Cuddesdon, priest, born October 2

1921; died July

11 2000

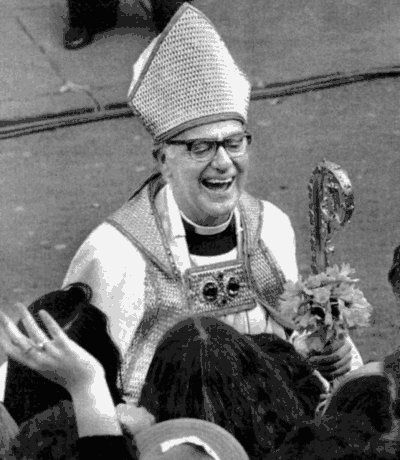

Canterbury

25th March, 1980

Today, in Canterbury, the Church put on

Her festal garb and colourful array

To celebrate the coming to his throne

Of Robert, called by God in this our day

To lead and serve with apostolic care

Those Christians, far dispersed in many

lands,

Who find their focus in Augustine's Chair

And now for Robert lift up praying hands.

Through crowded choir and nave, while

organ pealed,

A humble man with shepherd's staff he

trod,

Whose poise and simple dignity revealed

The strength of one who knew the peace of

God:

And when he raised his hand and voice to

bless

We caught the accents of Christ's

tenderness.

Robert Winnett

Page

Update:

March 2005

The

Runcie Memorial Window at Saint Faith's Church, Great

Crosby

To commemorate Robert Runcie's long

association

with our church, we commissioned and installed a double-light

window alongside

the western porch of the church. Here it looks out on to the

busy A565

highway and the 'Saint Faith's' bus-stop, and is lit in all its

colourful

splendour by the sunshine of afternoons and early evenings. The

window,

whose details may be seen in the photographs below, show Robert

Runcie,

St Faith's, St Luke's, Crosby, Merchant Taylors' School, St

Albans Cathedral

and Westminster Abbey, together with appropriate heraldry, the

Military

Cross - and, in the lower left hand corner, a pig, to celebrate

Lord Runcie's

life-time interest in pig-breeding (you can make it out in the

fourth picture!).

Bishop James Jones of Liverpool is seen at the dedication

service. Click

on any image to bring up a larger picture. For further

information, and

details of the inscriptions, see the article: 'Robert Runcie

R.I.P.' above.